May 26, 1903

(Wells, NV to Terrace, UT)

“This day, between Wells and Terrace, May 26, I had two experiences more interesting to read about than to pass through.

It is rather high altitude there, the elevation at Wells being 5,628 feet, and at Fenelon, the name of a side switch without a house near it, 20 miles east, the elevation is 6,154 feet.

There was a heavy frost on the ground in the morning when I left Wells at 6 o’clock, as, indeed, there was nearly every morning during that week. It was bitter cold, and before I had gone 20 miles my ears were severely frosted. There was no snow to rub on them though, and I had to doctor them the best I could with water first and then lubricating oil. In the afternoon of the same day it grew very hot, and my ears got badly sunburned, in common with my face. That gives an idea of the climate of the country.

The other experience of the day was not so painful; it would commonly be considered a treat; but it was a distinct shock to me because, not being in condition to use my wits properly, I did not understand.

I was about 70 miles east from Wells, near Tecoma, and riding on the finest stretch of trail that I had struck in several hundred miles, when I saw coming toward me in the distance one of the Conestoga wagons drawn by a team of horses with two men walking along beside the horses.

For those that don’t know the differences between a Conestoga and a normal covered wagon, this includes me…

A Conestoga Wagon was widely used for freighting. Their long boxes, large wheels, wide rims, and extra carrying capacity made them perfect for hauling large loads or multiple families. They were mostly used on the California, Santa Fe, and Old Spanish Trails, as the terrain was flatter and mostly sandy.

Conestoga wagons required between 6 and 10 oxen to pull them. The metal rims on the wheels for the Conestoga wagon were 4″ wide to float the weight of the wagon across long stretches of sandy trails.

Some Conestoga wagons were custom designed and built with double decks for special storage features. The average box length of a Conestoga wagon was 10 feet long and 4 feet wide. The sideboards could measure 4 feet high. Each wagon could carry up to 12,000 pounds of cargo.

The smaller more efficient Prairie Schooner was lighter, less bulky, and could turn a tighter circle than the Conestoga wagon. The boxes on the Prairie Schooner measured 4 feet wide by 8 feet long. The sideboards were only two feet high. Prairie Schooners only required between 2 and 6 oxen to pull them and could carry up to 2,500 pounds of cargo.

I was somewhat doubtful about the road I was following, afraid it would lead me too far from the railroad, and I was delighted to meet with someone who could tell me where the road led.

As the wagon approached it was lost to sight behind a bunch of sagebrush in a turn of the road. I kept riding toward it, and when I got to the spot there was nothing there. The desert was all about, devoid of any human being except myself, and there was no place behind a cliff or any hollow of the land where a team and wagon could disappear.

I was dumb with amazement, and dismounted in a daze, wondering if the sun had affected my head. My mind could not have been working clearly, for I never thought of its being a mirage, as I afterward knew it to be, I was afraid I was losing my mind, and went on silently with a feeling of dread. The stretch of road was of red gravel, and lasted 10 miles beyond the mirage. I covered it in 30 minutes. Then it began to rain, and I got back to the track and rode into Terrace, Utah, at 7:30 p.m. having covered 98 miles during the day of 13 hours.

G.Wyman

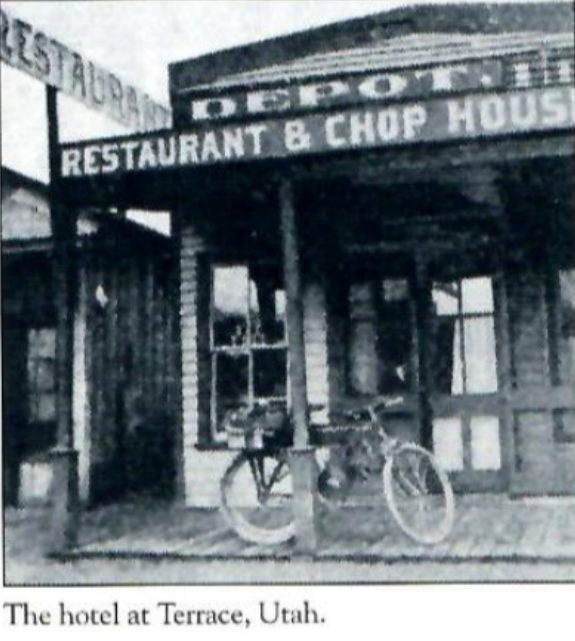

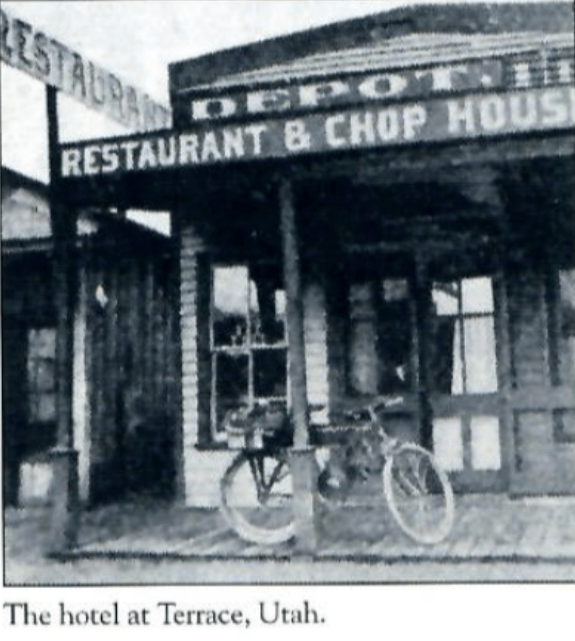

Terrace, where I stopped overnight on May 26, is in Utah, and is another division of some size. It is the biggest eating station on the Southern Pacific road between San Francisco and Ogden.

I crossed the line between Nevada and Utah when I was about 30 miles out of Wells, and at Terrace was about three-fourths of the way through the Great American Desert.

Around this place I saw the greatest collection of dugouts and log houses built of railroad ties that I had yet seen. Such dwellings are common on the outskirts of the division towns and in the settlements of section hands, but one sees only two or three at a time ordinarily, while at Terrace there is a swarm of them. For the dugouts the owners dig cellars about four feet deep and build up, criblike, four feet above the ground, giving the interior one or two rooms eight feet in height.

Foreigners mostly live in these and the tie houses, which are simply log shanties made of cross ties, and plastered up with adobe mud. Sometimes Indians of the blanket variety occupy these dugouts, but more often the aborigine stragglers from the reservations occupy tepees on the outskirts of the towns, if these places of a couple of dozen houses can be called towns.

*1903 image of an Indian Camp in Utah

While I saw plenty of Indians on my trip, I did not have any adventures with them. I did not have time to work up adventures; enough came without seeking; besides, the Indians I saw are not of the adventurous sort.

They are a lazy, dirty lot that sulk about while their squaws work in the eating houses and elsewhere to get money for extra tobacco for the bucks. The only time I spoke to an Indian during my trip was to ask a slouching fellow about a route and I could not understand his reply enough to derive any satisfaction. So that settles the Indian matter, for I don’t propose to manufacture any dime-novel incident just for the sake of adding color.”

May 27, 1903

(Terrace to Zenda, UT)

“It rained the night I stopped in Terrace, and, starting the next morning at 5:10 o’clock, I had to walk for several miles along the tracks; then I struck the desert, and found that the rain had left the sand hard enough to make good riding.

It was an uneventful day, and I made 104 miles, the road winding along the northern shore of the Great Salt Lake, of which I caught frequent glimpses.

Why did George go to the north of the Great Salt Lake? I-80 wasn’t built, obviously! I-80 was included in the original plan for the Interstate Highway System as approved in 1956. The highway was built in segments, with the final piece of I-80 completed in 1986 on the western edge of Salt Lake City.

If you look at the map in that era there is no other option but to go north

Bonneville Salt Flats and racing didn’t begin until 1912 – Racing happened on the legendary Bonneville Speedway before it even became a real track, back in 1912, with the first-ever land speed racing record set here just two years later in 1914.

Even though Pierce-Arrows and other early vehicles drove test these otherworldly, public lands salt flats and other racing events continued to happen here, the Bonneville Salt Flats didn’t gain world-renowned popularity until the 1930s when land speed racing pioneers Ab Jenkins and Sir Malcolm Campbell set new land speed records of 301 miles per hour.

I’ll throw in a little family history here, nothing to do with George Wyman but it’s a funny story…

My great uncle Leo, this is the write-up from the first page of his book

He spent a lot of time at Bonneville with Donald and Malcolm Campbell as their Chief Mechanic and Chief Engineer, I remember sitting on his knee and him telling me a story about Enzo Ferrari, of Ferrari Motorcars.

“Enzo came to see me and wanted me to go and work for him in Italy!”

– “You come to work for me and we will make the fastest cars together.”

“no thanks!” Leo laughed because he knew what was coming next, he said Enzo looked annoyed, so I figured why not annoy him more…

“You build cars that go at a good speed, but your cars are too slow…I’m going to build the fastest cars in the world, and break records!”

Leo was instrumental in the design and engineering to help Sir Malcolm Campbell and his son, Donald, set 10-speed records on land and 11 on water.

…back to George

I stopped 19 miles west of Ogden because it began to rain. I put up at a section house, that of the foreman of the gang, and he gave me a bed for the night. The railroad furnishes these section houses for the men, and I found them more comfy than I expected. There were no carpets, but the bed had a springy wire bottom, a good mattress and fine sheets. The hands do not fare like the foreman, though: they huddle together a dozen in a house in the other two buildings that constitute the “place.”

The place where I stopped is down on the time table as Zenda, but I was no prisoner there, and there was no romance to the situation. l am glad the foreman took me in, for a section gang is a motley lot, a regular cocktail of nationalities, and full of fighting qualities. At some of the places I passed I saw Chinamen at work on the railroads…

and this was a new thing to me accustomed, as I am, to the pigtails of the Pacific coast. It is not often that John engages himself in such arduous and un-remunerative labor.”

*The term ‘John’ – John Chinaman was a stock caricature of a Chinese laborer seen in cartoons of the 19th century. Also referenced by Mark Twain and popular American songs of the period, John Chinaman represented, in Western society, a typical persona of China. He was typically depicted with a long queue and wearing a coolie hat.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term first emerged with British sailors who, uninterested in learning how to pronounce the names of the Chinese stewards, firemen, and sailors who worked as part of their crews, came up with the generic nickname of “John”.

**Wyman is referring to the Chinese in Chinatown, San Francisco, image from 1904 in China Town

George’s route so far –

You must be logged in to post a comment.