May 31, 1903

(Granger to Bitter Creek, WY)

“Leaving Granger, which is a division town of about 200 people and has one hotel, at 6:30 o’clock in the morning…

The town today has less than half the population vs when George rode through, today it sits at about 94 people, and the only original building in both eras that I could find is the schoolhouse

even though it looks nothing like it did in 1903 I’m told the building was remodeled numerous times not knocked down and reconstructed

I found the road to Marston terribly rocky, and I returned to my old love, the crossties, after going half the distance, or about six miles. At Marston I found the old stage road to Green River, and many portions of this are gravelly and fine. Green River is quite a place with a population of about 1,500, * (11,262 in 2023) but I did not stop there. I pushed on past the famous castellated rocks to Rock Springs, 45 miles from Granger, and, arriving there at 11:45, I stopped for dinner.

*When George says Dinner, this is actually lunch, and supper is his evening meal, just for clarification of timing during the day.

Downtown Green River, WY

You always eat dinner in the middle of the day in this part of our glorious country, and if you get up with the sun and bump on a motorcycle over the hallways of the Rocky Mountains, you are ready for dinner at 12 o’clock sharp, and before. At Rock Springs the country begins to look upward again, the elevation there being 6,260 feet, 200 feet more than at Green River. From Rock Springs on, except for one drop of 500 feet from Creston to Rawlins and Fort Steele, there is a steady rise to the summit, about half way between Laramie and Cheyenne. There the elevation is a cool 8,590 feet.

Rock Springs, where I had dinner, is in the district of the Union Pacific Company’s coal mines. It is memorable for labor troubles and murders of Chinamen. I had the ends of my driving belt sewed at Rock Springs, and set out again past Point of Rocks, 25 miles east to Bitter Creek.

Rock Springs Railroad station today

East of Point of Rocks the road Is fairly level, but it is of alkali sand, and when I went over it, it was so badly cut up that in some places I had to walk.

Point of Rocks was a stagecoach stop, the building is still there up a dirt road, about 1/2 mile off the main road, easy to miss if you didn’t have a waypoint!

Bitter Creek might well be called Bitter Disappointment. I do not mean the stream of water that the road follows, but the station of the same name. It is one of those places which well-illustrates what I have said about the folly of taking the map as a guide in this country. About one-third of the “places” on the map are mere groups of section houses, while a third of the remainder are just sidetracking places, with the switch that the train hands shift themselves, and a signboard.

Bitter Creek belongs to the former class. The “hotel” there is an old boxcar. Yet, if you take a standard atlas you will find the name of Bitter Creek printed in big letters among a lot of other “places” in smaller type. The big type, which leads you to think it must be quite a place, means only that the railroad stops there. The “places” in smaller type are mere sidetracking points.

The boxcar is fitted-up as a restaurant and reminds one faintly of the all-night hasheries on wheels that are found in the streets of big cities. The boxcar restaurant at Bitter Creek, however, has none of the gaudiness of the coffee wagons. Still, I got a very good meal there.

When I cast about for a place to sleep it was different, but I finally found a bed in a section house. This experience was one of the inevitable ones of transcontinental touring. It was 7:15 o’clock when I reached Bitter Creek Station and it is 69 miles from there to Rawlins, the first place where I could have obtained good accommodations.”

June 1,1903

(Bitter Creek to Walcott, WY)

“After having breakfast in the boxcar restaurant, I left Bitter Creek for Rawlins. In this stretch, about 20 miles from Bitter Creek, I crossed my third desert, the Red Desert of Wyoming. It takes its name from the soil of calcareous clay that is fiery red, and the only products of which are rocks and sagebrush, and they will grow anywhere.

There is a Red Desert Station on the map, but there is nothing there but a telegraph office, and the same is true of Wamsutter and Creston, the succeeding names on the map. I took a snapshot of the road in the desert near Bitter Creek and wrote on the film: “Who wouldn’t leave home for this?”

East of Red Desert the road improved considerably, and from Wamsutter to Creston it was really fine.

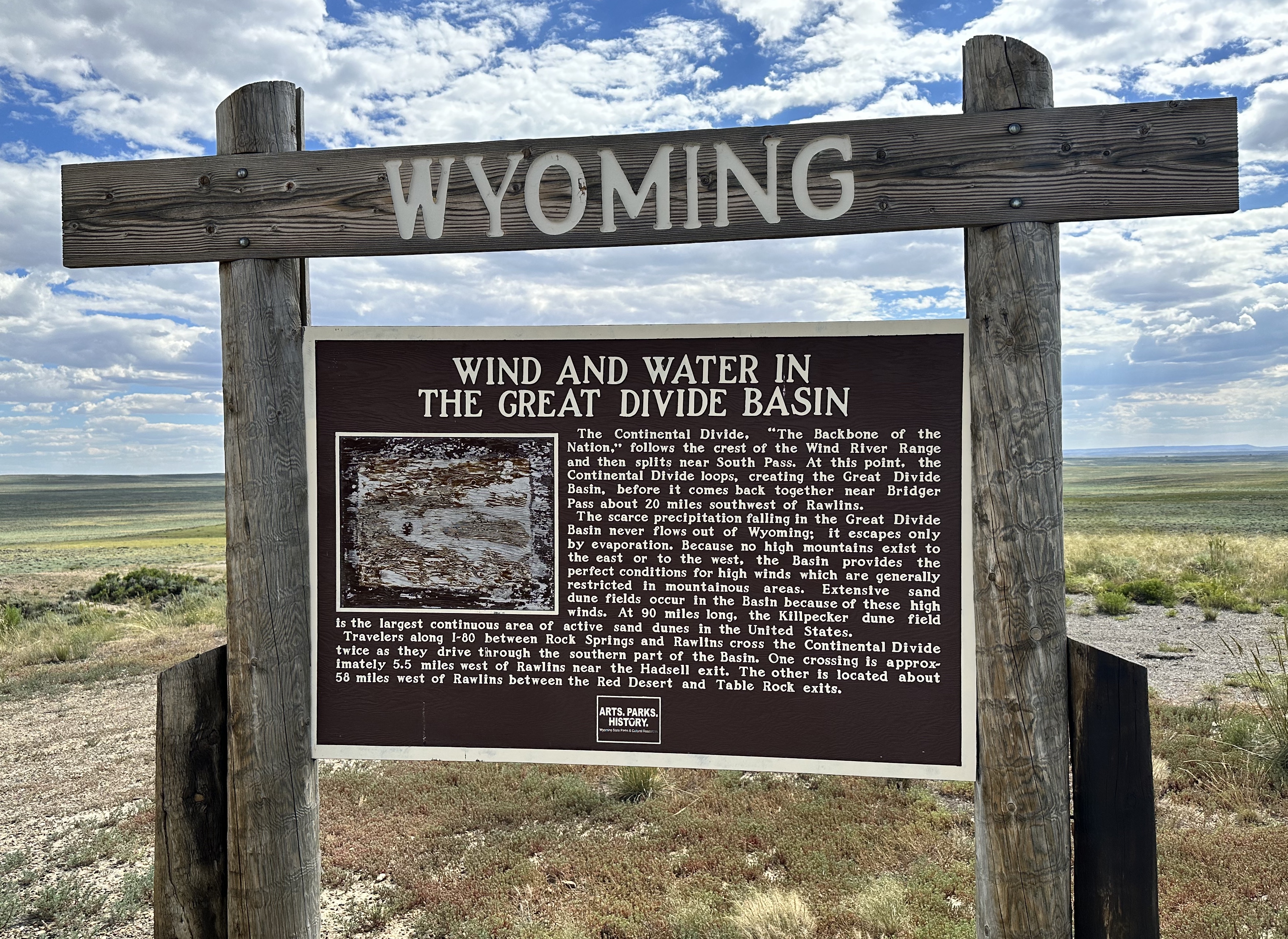

It was along this fine stretch, just before reaching Creston, that I came to the Great Divide and took a picture of the signpost, which marks the ridgeline of the great American watershed.

Standing there and facing the north, all the streams on your left flow to the west and all those on the right side flow toward the east, the waters of the former eventually finding their way to the Pacific, and the latter to the Mississippi River. This is the backbone of the continent and it is duly impressive to stand there and gaze at the official sign.

It does not mark the exact middle of the continent though, as some have mistakenly thought. It is about 1,100 miles east of San Francisco. I had rather expected to find the continental divide, if I did come across it, on the summit of a mountain, in a very rough piece of country, but it is in a broad pass of the Rockies, that seems more like a plain than a mountain, although a commanding view is obtainable from there.

To the north are the Green, Febris and Seminole chains of mountains, and further, in the northwest is the Wind River range, and beyond that again the Shoshone range, while to the south are the Sierra Madres, all escalloping the horizon with their rugged peaks, here green, there shrouded in a purplish veil, and far away showing only a hazy gray of outline. One realizes that he is in the Rockies positively enough.

From Creston to Rawlins there is nearly 30 miles of downgrade, and, as it is a fairly good highway of gravel, I made lively time over it.

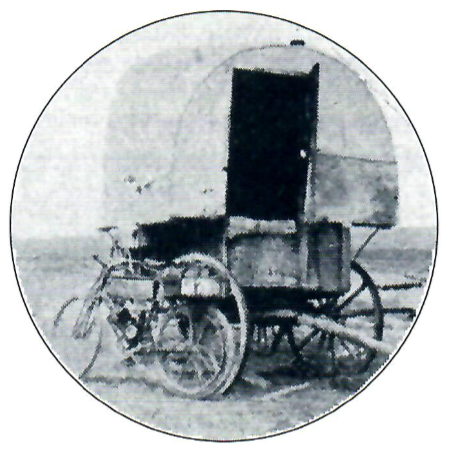

After leaving Creston there come Cherokee and Daly’s ranch before you get to Rawlins, and it was between these places, both mere railroad points, that I got the picture of the abandoned prairie schooner that was printed in Motorcycle Magazine.

Rawlins, where I stopped only for gasoline, is a town of some size, having more than 2,000 population. * (8413 in 2023)

Notice that church in the distance

From there the country becomes rolling again, and after passing Fort Fred Steele, I began to ascend once more. It is a great sheep ranch country all through here now from Rawlins. At Fort Steele there is nothing left but the ruins of abandoned houses.

I now follow the old immigrant trail that winds across the River Platte, and am fast approaching the Laramie Plains, over which my route lies to the Laramie Mountains. Beyond Fort Steele I enter White Horse Canyon, which got its name, so the story goes, from an Englishman, one of the sort known in the West as “remittance men,” who drank too much “Old Scratch,” and, mounted on a white horse, rode over the precipice and landed on the rocks 200 feet below.

At 6:10 p.m. I reached Walcott, a “jerkwater” settlement, composed of two saloons, a store and a railroad station. It is made important, though, by the fact that two stage lines come in there.

The hotels at places of the sort are generally clean, and they are kept more-or-less peaceable by the policy of reserving an out-building for the slumbers of the “drunks,” so I concluded to tarry.

I found some interest in automobiles here, and, after inspecting my machine, the natives fell to discussing the feasibility of running automobiles on the stage lines, instead of the old Concord coaches, drawn by six horses, that are now used. One of the stage drivers said that if anyone would build an automobile that would carry 12 or 14 persons and run through sand six inches deep. He would pay from $3,000 to $5,000 for it. I told him to wait awhile.

After supper I mended my broken spokes with telegraph wire, and entertained quite a group of spectators, who watched the job with open curiosity. I find a variable reception in this country to my statement that I have journeyed from San Francisco, and am bound for New York. A great many do not believe me, and smile as if amused by an impromptu yarn.

There is another class, though, that of the old settlers, the real mountaineers who have had adventures of all sorts in the mountains and the wilderness. These men are surprised at nothing, and they rather nettle me by accepting me and my motor bicycle and my statement with utmost stolidity as if the feat was commonplace. For awhile I thought that this class, too, were unbelievers, but later I learned that as a rule they are the only ones who do believe me, because they are men who believe anything possible in the way of overland journeying.”

San Francisco to Walcott, WY

continued…

You must be logged in to post a comment.